Yanasa TV News

How a Century-Old Water Project Left Potter Valley’s Farmers High and Dry in the Name of Saving Salmon

A Valley in Shock

In early August 2025, farmers and ranchers in Northern California’s Potter Valley woke to the worst possible news: the water that has irrigated their hayfields, vineyards, orchards, and pastures for over a century was gone.

No trickle through the canals. No flow past the intakes. Just dry gravel beds where the East Branch Russian River should have been.

It was peak summer heat — two months before harvest — and in the thick of fire season. Without irrigation, crops would wither and cattle would need to be sold or slaughtered early. One rancher summed it up bluntly:

“The shutoff came without warning. We had irrigation schedules, planting plans, and contracts based on flows that have always been there. In one decision, it was all gone.”

— Vineyard manager, Potter Valley Irrigation District

The Potter Valley Project: A Century of Shared Water

To understand the shock, you have to understand the system.

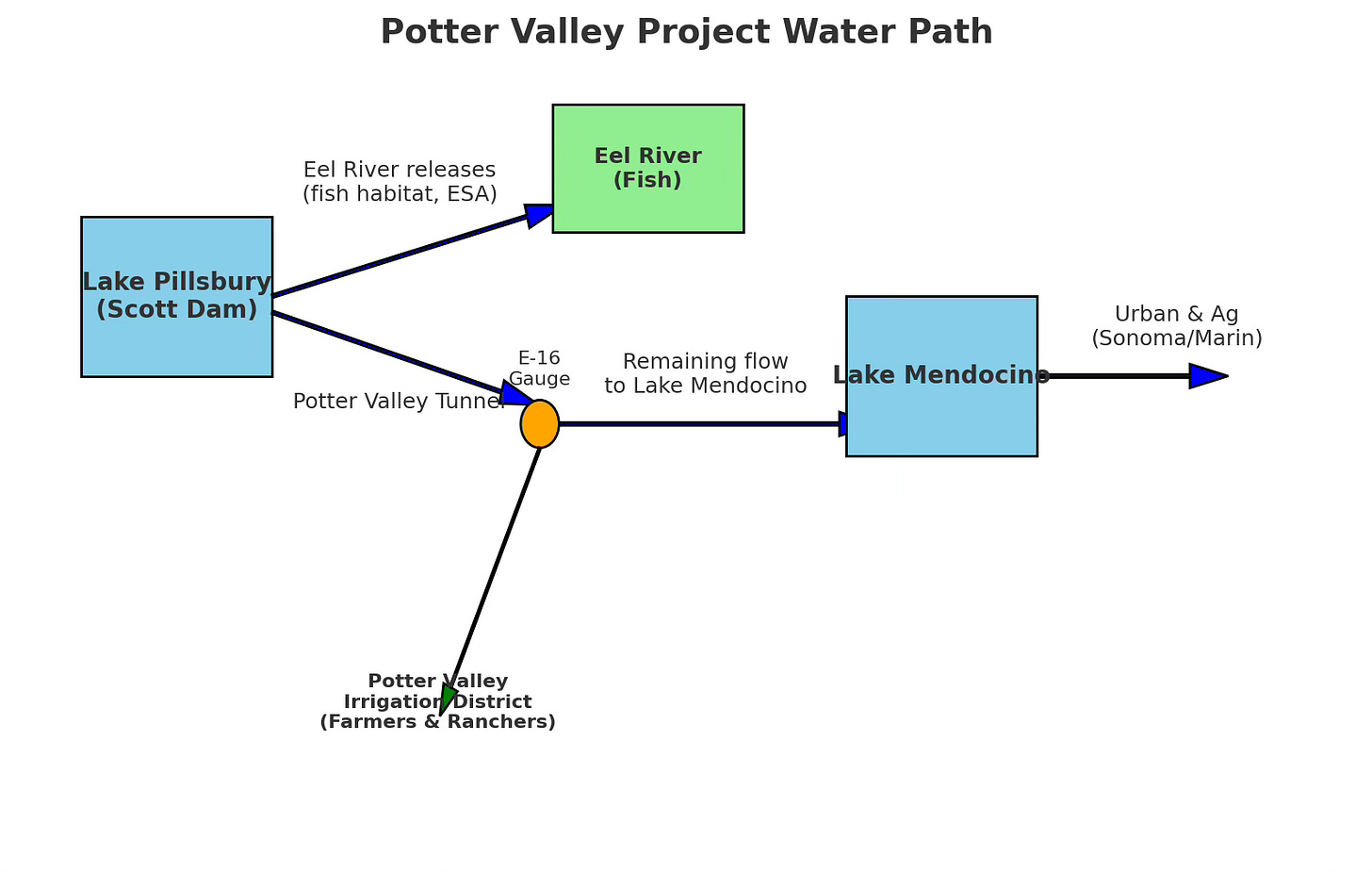

The Potter Valley Project is a century-old hydropower and water diversion scheme on the upper Eel River, built in 1908. It consists of:

- Scott Dam (impounds Lake Pillsbury)

- Cape Horn Dam (diversion point into the Potter Valley Tunnel)

- A tunnel and powerhouse that drop water into the East Branch Russian River.

From there:

- Potter Valley farmers and ranchers take their irrigation water.

- The remaining flow continues downstream to Lake Mendocino, where it supplies urban and agricultural users in Sonoma and Marin counties.

For more than 100 years, this setup has moved “Eel River water” south into the Russian River basin — supporting both rural agriculture and city taps far from the Eel’s headwaters.

“We’ve been irrigating from this water for generations. Now, with the lake still a third full, we’re told there’s nothing for us — not even enough to finish the season. It’s hard not to feel like we’ve been written out of the picture.”

— Local hay and cattle rancher, Potter Valley

The August 2025 Cutoff: What Actually Happened

In February 2025, PG&E asked the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for a temporary flow variance. They argued that late-summer inflows into Lake Pillsbury would be so low that they needed to:

- Reduce the minimum diversion flow through the tunnel into the East Branch (irrigation side).

- Conserve the cold-water pool in the lake to meet fish habitat and temperature requirements in the Eel River.

On August 4, FERC approved the variance — lowering the required diversion at the E-16 compliance gage to as little as 5 cubic feet per second.

Three days earlier, PG&E had already reported to FERC that E-16 flows (Potter Valley diversion side) were below even those reduced targets — meaning Potter Valley’s diversion was effectively throttled to nothing.

“The Endangered Species Act doesn’t give us the option to choose irrigation over survival of a listed species. When water is scarce, the law is clear — fish flows have to be met.”

— Federal Energy Regulatory Commission compliance officer

Where Does the Water Normally Go?

When the diversion was cut:

- Farmers at the first intake (Potter Valley) lost supply immediately.

- Downstream cities didn’t see an “optics bump” — Lake Mendocino also fell slightly.

- The water conserved stayed in Lake Pillsbury for Eel River releases and dam safety needs.

The “Did They Have To?” Question

Locals look at 35,000 acre-feet in the lake and ask: Why couldn’t we have had some?

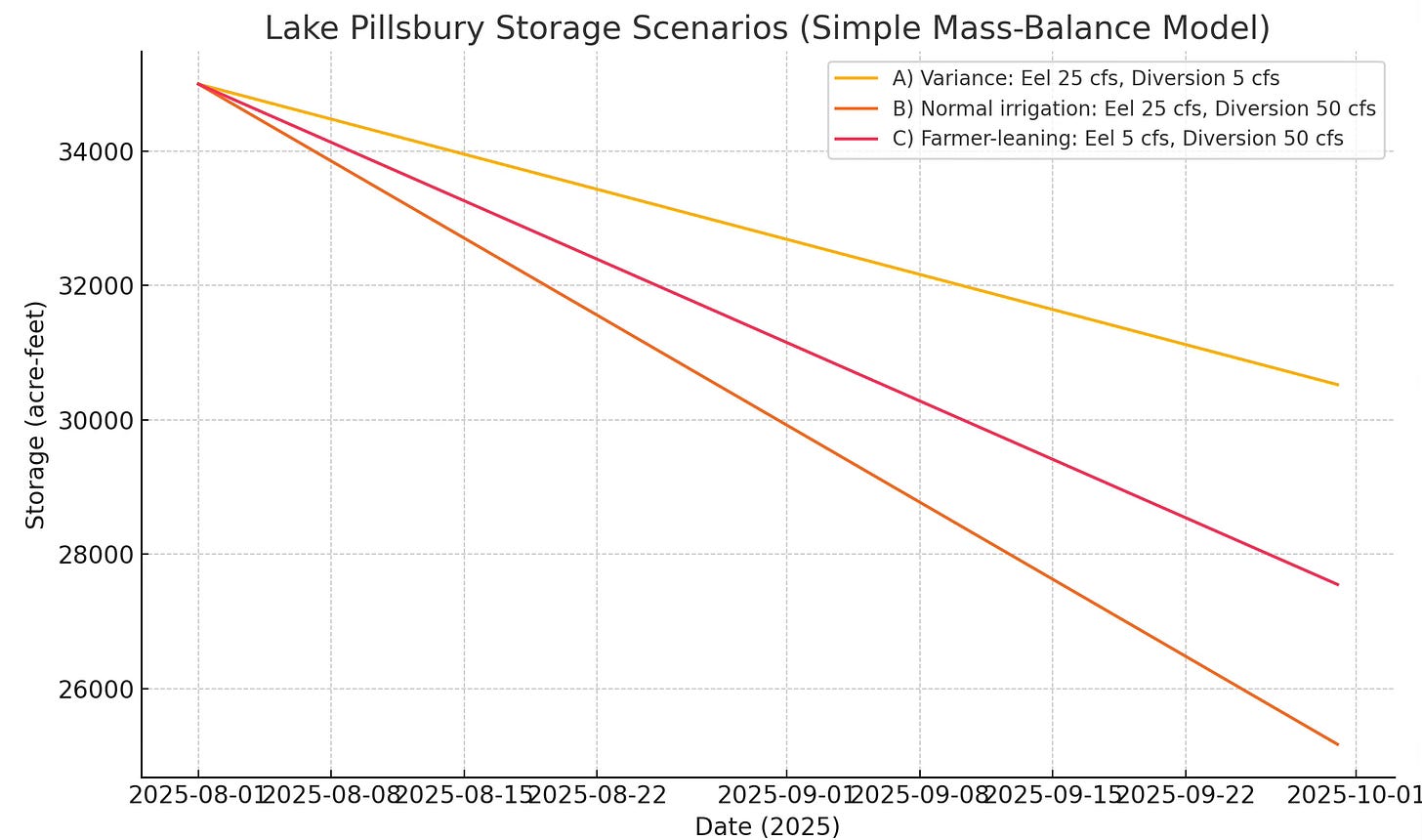

To explore that, I modeled what would happen if irrigation flows had continued in August and September at historic rates.

Model Scenarios (Aug 1–Sep 30):

- Variance mode: Eel River release 25 cfs, irrigation diversion 5 cfs

- Normal irrigation: Eel River release 25 cfs, irrigation diversion 50 cfs

- Farmer-leaning: Eel River release 5 cfs, irrigation diversion 50 cfs

Results:

Even in the “normal irrigation” case, Pillsbury wouldn’t have run dry — but it would have dropped 2.5× faster, leaving much less “cold-water buffer for fish” and less margin if a hot spell or wildfire required emergency releases.

“I’m not against saving fish. But we need a plan that saves farms and fish. Right now, we’ve got one that saves fish and kills farms.”

— Fourth-generation rancher, Potter Valley

Why the Eel River Gets Priority

Three overlapping layers of law make the Eel River the legal priority over irrigation in drought:

- Federal Endangered Species Act (ESA)

Protects threatened Chinook salmon, steelhead trout, and endangered coho salmon. ESA “takes” (harm) are strictly prohibited. - FERC License Conditions

Incorporate ESA biological opinions into operating rules, making fish flow and temperature targets enforceable. - California Law

The state’s own endangered species act, water quality standards, and seasonal flow requirements reinforce the federal rules.

“These fish populations are on the brink. If we lose the cold-water pool now, we risk losing an entire year class of salmon — and that could push the species closer to extinction.”

— NOAA Fisheries biologist, Eel River recovery program

How Rising Seismic Risks Add Pressure to Lake Pillsbury’s Future

While environmental compliance was the stated driver behind the August 2025 irrigation cutoff, dam safety concerns quietly loom in the background of every operational decision at Lake Pillsbury. Scott Dam, built in 1921, sits within reach of the Bartlett Springs Fault Zone, a known seismic hazard capable of producing strong earthquakes. The structure predates modern seismic engineering standards, and PG&E’s own filings with federal regulators have acknowledged its vulnerability in a major quake scenario. Maintaining higher late-summer storage levels is not just about preserving a cold-water pool for salmon — it also provides an operational buffer, ensuring there is enough water to release quickly if the dam’s integrity were threatened by seismic activity or a sudden slope failure. This dual-purpose safety margin means that reducing irrigation demand can serve both environmental goals and emergency readiness, even if it comes at a steep cost to local agriculture.

In recent years, seismic activity along the Pacific Rim — the vast tectonic “Ring of Fire” encircling the Pacific Ocean — has shown an uptick in both frequency and intensity, and Northern California has not been immune. The Bartlett Springs Fault Zone, which runs near Scott Dam, has recorded a series of small to moderate earthquakes in the past two decades, reminding geologists that the region remains seismically active. While many of these quakes are too small to cause structural damage, they serve as indicators of underlying tectonic stress that could, under the right conditions, trigger a larger event. Across the broader Pacific Rim, significant earthquakes in Alaska, Japan, and Chile have heightened awareness that fault systems are interconnected through complex plate dynamics. For an aging dam like Scott, sitting squarely in an earthquake-prone corridor, even a modest regional jolt could test the limits of a century-old design — a risk factor that weighs heavily in both water management decisions and the debate over whether the dam should remain in place at all.

Why Cutoff Feels Wrong for Farmers

For Potter Valley growers, the August cutoff was a gut punch:

- It came with little practical warning, right before harvest.

- They see a reservoir with tens of thousands of acre-feet and believe some water could have been spared without devastating fish.

- They already operate in a fragile farm economy — feed prices, labor shortages, climate pressures — and the sudden loss of irrigation threatens their survival.

“They talk about conserving water, but the fish don’t eat hay, and the fish don’t pay my bills. We’re trying to feed people and keep our community alive — and that matters too.”

— Dairy farmer, Mendocino County

Longer-Term Stakes and Dam Removal

PG&E has filed to surrender its license and remove both Scott Dam and Cape Horn Dam. If that happens:

- Lake Pillsbury will vanish.

- Diversions to Potter Valley and Lake Mendocino will cease unless a new fish-friendly diversion is built and operated by someone else.

“The Eel River has been sacrificed for over a century to feed water south. This variance was about giving it a fighting chance during a critical summer period.”

— California Department of Fish & Wildlife spokesperson

For Potter Valley agriculture, this is more than a bad summer — it’s a preview of a possible permanent shutoff.

Farmers vs. Environmental Policy

Potter Valley isn’t alone. Around the world:

- Dutch, Irish, and Canadian farmers have protested nitrogen emission caps and land buyouts.

- Australian irrigators fought Murray-Darling Basin environmental flow rules.

- In the U.S., Klamath Basin farmers have faced repeated irrigation shutoffs for fish.

Critics see these as part of a “rewilding” agenda — prioritizing ecological restoration over food production, sometimes at the cost of rural livelihoods.

“This isn’t about taking water for cities or about optics. This is about ensuring that when fall comes, the river still has cold, oxygen-rich water for salmon to spawn. Without that, there’s no recovery.”

— Regional Water Quality Control Board staff scientist

The Trade-Off

- Keeping irrigation running this summer:

- Helps farmers finish the season.

- Speeds drawdown of Lake Pillsbury, reducing the cold-water pool for endangered fish.

- Risks noncompliance with ESA and license terms.

- Cutting irrigation:

- Protects fish habitat and satisfies environmental law.

- Leaves rural communities without water at the peak of need.

A Valley at a Crossroads

In Potter Valley, a century-old relationship between farms and rivers is collapsing under the weight of modern environmental law, climate alarmism, and corporate retreat.

The August cutoff wasn’t about optics or urban greed. It was the collision of two legal obligations: keep endangered fish alive, and deliver water to farmers. In 2025, fish won.

Whether that’s good stewardship or a sign of a system that no longer values rural agriculture depends on where you stand. But one thing is certain: if nothing changes, this summer’s shutoff is just the beginning.

Potter Valley Project – Environmental & Legal Timeline

1908 – Project Construction

- Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) completes the Potter Valley Project:

- Scott Dam creates Lake Pillsbury on the Eel River.

- Cape Horn Dam diverts water through a tunnel into the East Branch Russian River.

- Original purpose: hydroelectricity and water diversion for agriculture.

1960s–1980s – Environmental Awareness Grows

- Declines in Eel River salmon and steelhead populations draw attention from biologists and environmentalists.

- State and federal agencies begin documenting water diversion impacts.

1986 – Endangered Species Protections Begin

- Winter-run Chinook salmon listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA).

- Steelhead trout and coho salmon later receive ESA protections (threatened or endangered).

1990s – ESA Litigation Expands

- Environmental groups sue PG&E and regulators over diversion flows and fish mortality.

- NOAA Fisheries and California Department of Fish & Wildlife (CDFW) develop stricter biological opinions requiring minimum Eel River flows and temperature standards.

2004 – FERC License Renewal Battle

- PG&E’s 50-year license for the project comes up for renewal.

- Negotiations result in increased Eel River minimum flows and more detailed temperature monitoring to protect fish.

- Irrigation deliveries remain but are now explicitly subordinate to environmental flow requirements.

2019 – PG&E Bankruptcy & Decision to Exit Project

- Facing billions in wildfire liabilities, PG&E files for bankruptcy.

- PG&E announces it will not seek a new long-term license for the Potter Valley Project, citing costs and environmental obligations.

2020 – License Transition & Decommissioning Process Begins

- FERC issues annual licenses while PG&E prepares a license surrender and decommissioning plan.

- Regional agencies form the Eel-Russian Project Authority to explore a fish-friendly diversion replacement.

Feb 14, 2025 – PG&E Requests Flow Variance

- PG&E petitions FERC for a temporary variance to reduce minimum diversion flows (E-16) to conserve Lake Pillsbury’s cold-water pool for fish.

- Cites low projected inflows, ESA obligations, and water temperature management in the Eel River.

July 28, 2025 – FERC Questions Variance

- FERC requests clarification on PG&E’s operational plans before granting the variance.

Aug 3, 2025 – PG&E Reports Diversion Deviation

- PG&E files a notice with FERC that E-16 flows (Potter Valley diversion side) are below even reduced targets.

- Farmers and ranchers effectively lose irrigation supply overnight.

Aug 4, 2025 – FERC Approves Variance

- FERC authorizes reduced diversion minimums down to 5 cfs at E-16.

- Goal: retain storage in Lake Pillsbury to meet Eel River fish flow and temperature requirements.

July 25, 2025 – License Surrender Application Filed

- (Filed slightly earlier than the variance approval) PG&E formally applies to surrender its license and remove both Scott Dam and Cape Horn Dam.

- If approved, Lake Pillsbury will be drained, and diversions to Potter Valley/Lake Mendocino will cease unless a replacement system is built.

The Present

- Farmers face immediate losses from the 2025 cutoff.

- Long-term future hinges on whether new infrastructure can replace the diversion after dam removal.

- Environmental law remains clear: ESA and state protections require prioritizing Eel River fish habitat over irrigation in drought conditions.

The facts regarding Lake Pillsbury and the Scott Dam diversion are misleading. Water diversions are from the “project water” that stores snow melt. The natural in -stream flows are nearly non-existent by mid-summer. Salmon spawn in the mainstream and the smolt move down stream in late spring. Steelhead spawn upstream where there is year around flows. Below Lake Pillsbury the salmon and steelhead populated an area known as “blue slide”. The area was over fished for “trout”, and poaching was extreme. Still year after year the fish survived in the cold-water release from Pillsbury. It was not until the complete closing of the logging road, limiting access to this section of river did the small fish have a chance for survival.

Fish counts hit a 60 year high for both Salmon and steelhead. Fish and Game counts are online Van Aresdale fish ladder.

The diversion enhances the fish populations on the Russian River, that are not discussed. No reliable fish studies are valid, since the biologist’s report are not honestly peer revied by the “fish-bio community”.

Fish counts F&G Vanarsdale Ladder 60-year high was in 2003.